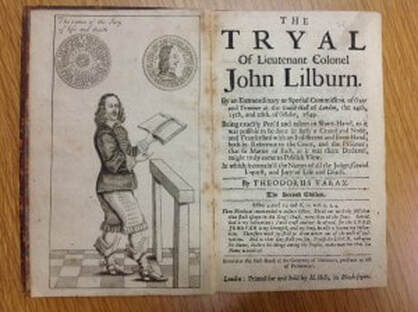

John Lilburne, or "Freeborn John" was a colonel, political agitator, and life-long malcontent in mid-17th century England. The question is to what degree he and his Levellers influenced the short- and long-term development of the English and later British political system. John Lilburne, or "Freeborn John" was a colonel, political agitator, and life-long malcontent in mid-17th century England. The question is to what degree he and his Levellers influenced the short- and long-term development of the English and later British political system. Long dead is the historiographical interpretation that the British colonists in North America developed autonomously. The major works of historians like David Hackett Fischer have demonstrated that the colonists who came from England and later Britain, brought with them distinctly British ideas about the world.[1] Fischer, in particular, argued convincingly that the cultural practices and identities of whole communities in Britain were transplanted to the New World. That they developed differently than they otherwise might have in the British Isles once arrived is also indisputable. Even the Eastern Coast of North America, was at one point, the western frontier of the British Empire, and therefore subject to the conditions of Frederick Jackson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis.”[2] However, what is no longer much disputed is the fact that the British North American colonies developed and responded to these conditions in British ways.[3] It is within this general framework that major explanations for the origins of the American Founding are developed. J.G.A. Pocock’s, “Republican Synthesis,” falls into such a category. Pocock argued and has continued to defend for almost half a century, the idea that a major influence upon the Framers of the Constitution and the Founding generation of Americans was the republican ideology expressed by British writers and thinkers.[4] Pocock claimed that James Harrington’s Oceana was an important intellectual pathway that took the ideas of Roman Republicanism, and via Machiavelli’s works, translated those ideas into an English context. Through further translations, like the important works of Trenchard and Gordon’s Cato’s Letters, these ideas were consumed and adapted by the American Framers for their American geopolitical realities. Bernard Bailyn’s prize-winning research significantly deepened this understanding by evaluating the political literature disseminated by the American colonists.[5] However, the republican influence was only one ideological influence on the British colonists. The ideas of corruption, civic virtue, and republican representation was only one strain of British thought synthesized by Madison and the Framers into the American Constitution. There was also a significant ideological commitment to individual liberties, and the protection of these liberties within a negative constitutional framework. It has typically been assumed that these ideas originated with the social contract theory expressed in John Locke’s Treatises on Government. This assumption ignores the reality of a political group that not only pre-dated Locke, but whose rhetoric was more in line with the liberal tradition expressed in American Framing documents like the Bill of Rights. Exactly where the Levellers fit into the historiographical interpretations of the turmoil of the 1640’s has been an open question of scholarship in the last century. Early interpretations of the 20th century were excited about the discovery of the true genesis of the liberal tradition within Western Civilization. These interpretations were significantly tempered during the rise of the revisionist historians of the mid-century, almost to the point of relegating them once again to ideological and political obscurity within the narratives of 17th century England. Emerging research in the last twenty years has resurrected interest in the Levellers and has begun to show that they were an important influence in the development of England’s political identity. Since it is now commonly accepted that British ideas had a profound influence on the Founders, then the question which has not been asked but begs the asking is: to what degree did Leveller ideas influence the colonists in British North America? Impact can be a problematic concept for the historian to evaluate, particularly since some individuals or groups deliberately or accidentally misunderstood historical arguments made by others. One way to attempt to answer this question is to evaluate the political literature disseminated by a particular group and to evaluate the semantical strategies employed. To evaluate the Levellers, the historian is blessed with a plethora of primary source material for this purpose, since the Levellers were prolific writers, and the English political context of the 1640’s allowed for a flood of pamphlets and broadsides. By evaluating the Leveller lexicon, the historian can then identify critical re-definitions or colloquialisms introduced by the Levellers, and subsequently used by other groups within the wider British world. Several incidental research particulars are then available to the historian. The first is to determine exactly which principles the Levellers were committed to, and how they described those principles. Additionally, the influence that this lexicon had on British society in general is a fruitful and unexplored vein of historical inquiry. As just one example, although Trenchard and Gordon were influenced by Harrington’s republican commitments and Machiavelli’s fear of corruption, they frequently used vocabulary which was similar to that of the Levellers. This could demonstrate direct influence, or that the Levellers had infused their own terminology into all British natural rights discussions through the discourse of the 1640’s. Either way, when demonstrated, it connotes influence. Finally, how did Leveller language come to be used in British North America? These may have been encoded in republican thought like Cato’s Letters, liberal ideology like Locke’s Treatises on Government, or could have been more direct, in documents like Bacon’s Declaration of the People, or the Maryland Toleration Act (1649), which was authored at the height of Leveller influence in England. It is through the evaluation of the Leveller influence on the natural rights vocabulary of the British world that the answers to these questions will become better understood. The author has conducted numerous research projects related to natural law and the Levellers throughout many of the courses included in the graduate program at Liberty University. These research topics have ranged from reseach projects on natural law expressed in the English Wars of the Roses to the history of natural law within British political thought from 1600-1800, The author has also conducted research into the ways in which John Lilburne and the Levellers' ideological commitments to the freedom of religion and natural law was influenced by their Protestant religious ideology. Even outside of this particular field, the author has explored the implications of natural law in areas such as the Standard Oil antitrust case, and designed an outline for a course on Revolutionary 17th century England. [1] Fischer, David H. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. [2] Turner, Frederick J. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Speech. American Historical Society, Chicago: July 12, 1893. [3] Another way to conceive of this reality is to imagine a continuum, upon which are all of the potential ways in which a society might evolve, if exposed to different conditions. The British society in North America, due to a different set of circumstances, developed differently than it might or would have in the Old Country. Of course, as a historian, one must not be concerned with what might have happened, but rather what did. [4] Pocock, J. G. A The Machiavellian Moment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975. [5] Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorNathan Gilson is a Social Studies Teacher in South Carolina with over 10 years of experience in the public school systems. He has taught US and World History courses, and is currently working toward a Ph.D. in History from Liberty University. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed