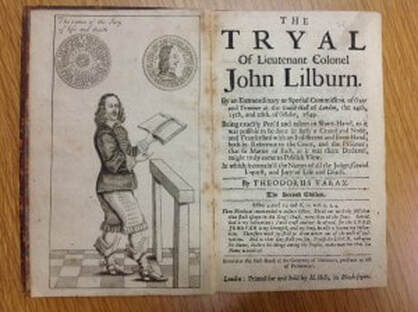

John Lilburne, or "Freeborn John" was a colonel, political agitator, and life-long malcontent in mid-17th century England. The question is to what degree he and his Levellers influenced the short- and long-term development of the English and later British political system. John Lilburne, or "Freeborn John" was a colonel, political agitator, and life-long malcontent in mid-17th century England. The question is to what degree he and his Levellers influenced the short- and long-term development of the English and later British political system. Long dead is the historiographical interpretation that the British colonists in North America developed autonomously. The major works of historians like David Hackett Fischer have demonstrated that the colonists who came from England and later Britain, brought with them distinctly British ideas about the world.[1] Fischer, in particular, argued convincingly that the cultural practices and identities of whole communities in Britain were transplanted to the New World. That they developed differently than they otherwise might have in the British Isles once arrived is also indisputable. Even the Eastern Coast of North America, was at one point, the western frontier of the British Empire, and therefore subject to the conditions of Frederick Jackson Turner’s “Frontier Thesis.”[2] However, what is no longer much disputed is the fact that the British North American colonies developed and responded to these conditions in British ways.[3] It is within this general framework that major explanations for the origins of the American Founding are developed. J.G.A. Pocock’s, “Republican Synthesis,” falls into such a category. Pocock argued and has continued to defend for almost half a century, the idea that a major influence upon the Framers of the Constitution and the Founding generation of Americans was the republican ideology expressed by British writers and thinkers.[4] Pocock claimed that James Harrington’s Oceana was an important intellectual pathway that took the ideas of Roman Republicanism, and via Machiavelli’s works, translated those ideas into an English context. Through further translations, like the important works of Trenchard and Gordon’s Cato’s Letters, these ideas were consumed and adapted by the American Framers for their American geopolitical realities. Bernard Bailyn’s prize-winning research significantly deepened this understanding by evaluating the political literature disseminated by the American colonists.[5] However, the republican influence was only one ideological influence on the British colonists. The ideas of corruption, civic virtue, and republican representation was only one strain of British thought synthesized by Madison and the Framers into the American Constitution. There was also a significant ideological commitment to individual liberties, and the protection of these liberties within a negative constitutional framework. It has typically been assumed that these ideas originated with the social contract theory expressed in John Locke’s Treatises on Government. This assumption ignores the reality of a political group that not only pre-dated Locke, but whose rhetoric was more in line with the liberal tradition expressed in American Framing documents like the Bill of Rights. Exactly where the Levellers fit into the historiographical interpretations of the turmoil of the 1640’s has been an open question of scholarship in the last century. Early interpretations of the 20th century were excited about the discovery of the true genesis of the liberal tradition within Western Civilization. These interpretations were significantly tempered during the rise of the revisionist historians of the mid-century, almost to the point of relegating them once again to ideological and political obscurity within the narratives of 17th century England. Emerging research in the last twenty years has resurrected interest in the Levellers and has begun to show that they were an important influence in the development of England’s political identity. Since it is now commonly accepted that British ideas had a profound influence on the Founders, then the question which has not been asked but begs the asking is: to what degree did Leveller ideas influence the colonists in British North America? Impact can be a problematic concept for the historian to evaluate, particularly since some individuals or groups deliberately or accidentally misunderstood historical arguments made by others. One way to attempt to answer this question is to evaluate the political literature disseminated by a particular group and to evaluate the semantical strategies employed. To evaluate the Levellers, the historian is blessed with a plethora of primary source material for this purpose, since the Levellers were prolific writers, and the English political context of the 1640’s allowed for a flood of pamphlets and broadsides. By evaluating the Leveller lexicon, the historian can then identify critical re-definitions or colloquialisms introduced by the Levellers, and subsequently used by other groups within the wider British world. Several incidental research particulars are then available to the historian. The first is to determine exactly which principles the Levellers were committed to, and how they described those principles. Additionally, the influence that this lexicon had on British society in general is a fruitful and unexplored vein of historical inquiry. As just one example, although Trenchard and Gordon were influenced by Harrington’s republican commitments and Machiavelli’s fear of corruption, they frequently used vocabulary which was similar to that of the Levellers. This could demonstrate direct influence, or that the Levellers had infused their own terminology into all British natural rights discussions through the discourse of the 1640’s. Either way, when demonstrated, it connotes influence. Finally, how did Leveller language come to be used in British North America? These may have been encoded in republican thought like Cato’s Letters, liberal ideology like Locke’s Treatises on Government, or could have been more direct, in documents like Bacon’s Declaration of the People, or the Maryland Toleration Act (1649), which was authored at the height of Leveller influence in England. It is through the evaluation of the Leveller influence on the natural rights vocabulary of the British world that the answers to these questions will become better understood. The author has conducted numerous research projects related to natural law and the Levellers throughout many of the courses included in the graduate program at Liberty University. These research topics have ranged from reseach projects on natural law expressed in the English Wars of the Roses to the history of natural law within British political thought from 1600-1800, The author has also conducted research into the ways in which John Lilburne and the Levellers' ideological commitments to the freedom of religion and natural law was influenced by their Protestant religious ideology. Even outside of this particular field, the author has explored the implications of natural law in areas such as the Standard Oil antitrust case, and designed an outline for a course on Revolutionary 17th century England. [1] Fischer, David H. Albion’s Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989. [2] Turner, Frederick J. “The Significance of the Frontier in American History.” Speech. American Historical Society, Chicago: July 12, 1893. [3] Another way to conceive of this reality is to imagine a continuum, upon which are all of the potential ways in which a society might evolve, if exposed to different conditions. The British society in North America, due to a different set of circumstances, developed differently than it might or would have in the Old Country. Of course, as a historian, one must not be concerned with what might have happened, but rather what did. [4] Pocock, J. G. A The Machiavellian Moment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975. [5] Bailyn, Bernard. The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967.

0 Comments

This is the story of one man and his community, and how together they brought an end to the Great Depression much earlier than the rest of the country. The story draws extensively from speeches by historians memorializing the efforts of the man and his company as well as company records and the words of those who worked for the man and his company. It also draws on business and national statistics, and principles of macroeconomic theory to set the story within a national context, hopefully to help the reader understand what makes this story truly remarkable.

Elliott White Springs took control of the Springs Cotton Mill industry in 1931, at the height (or depth if you prefer) of the Depression. Cotton mills were closing all over the country, but Springs kept his open, primarily as a service to his community. He had just inherited control of the company from his father, Leroy Springs, and the situation was bleak. According to Walter Y. Elisha, Springs “fought off creditors, the New Deal, union organizers and imports” while he “modernized the plants. . .[which] ran through the depression even when the warehouses were bulging with unsold goods.”[i] Springs stockpiled his goods “everwhere he could stick a piece of cloth” just to keep the mill opened.[ii] One unnamed employee gave Springs credit for running the mills “to give us three days a week. So we could live.”[iii] In many ways, Springs was simply continuing the legacy of his grandfather, Samuel White, who had founded the cotton mill in the wake of Reconstruction and the need among community members for employment.[iv] The business that Springs inherited was not well-positioned to weather the Great Depression. Springs’ father, Leroy Springs, had badly damaged the confidence of New York bankers by telling them that his son had no idea about the operation of the mills, and also buried the corporation in debt.[v] Many of the company holdings were also insolvent, in most cases in bankruptcy themselves, making it difficult for the company to raise the capital needed to remain open.[vi] The plants themselves had outdated equipment, and the business had been coasting on the general growth commonly referred to as "The Roaring 20's." Therefore, the Springs Cotton Mill company fit the typical narrative of an early Depression-Era business: It was a high risk creditor unable to obtain financing because it wasn’t safe enough of an investment, and its holdings were not liquid enough to be called upon in order to make up any short-falls. It was precisely this kind of debt that the banks could no longer afford to hold in the growing economic crisis of the early 1930’s.[vii] One of Springs' ownly saving graces was his ownership of the Bank of Lancaster, which provided all of the funding for his actions; and this was certainly key in allowing Springs to succeed where many others could not.[viii] Springs showed a tremendous ingenuity in keeping his cotton mills operating; all of which were in bad need of modernization. For those who were committed to keeping their plants opened as Springs was, the Depression was something of an opportunity in disguise. Springs purchased wholesale machinery, much of which was somewhat outdated itself, but still represented an upgrade to his own plants’ current inventory, at vastly discounted rates. A lot of the machinery came from closing or greatly reduced New England plants, responding to national trends which saw textile production shrink by 15% between 1929 and 1933.[ix] Equipment valued at $4,000 in 1950 was purchased for $30, Springs bought $1,000 looms for $25 each plus freight, and in one case he acquired equipment from a New England mill for free, provided that he was willing to dismantle and remove it from the property so that the original owner could avoid paying taxes on capital.[x] The end result was that when he finished outfitting his plants with new machinery, he “had one more cotton mill than when he started and more modern equipment everywhere.” Springs dedication to his mill workers (and therefore to the mills that employed them) was uncommon, and his mechanical intellect matched his dedication. Springs had a loom machine moved to the basement of his home and tinkered incessantly with it until he could completely disassemble and reassemble the whole apparatus.[xi] In part, Springs undoubtedly succeeded where others failed due to his non-compliance with federal regulations and union actions, both of which greatly curtailed the ability of his competitors to remain in business. After initial cooperation with federal regulation expressed in the Textile Codes of 1933, Springs quickly reversed course in 1934 and refused to report his production figures to the Textile Code Institute.[xii] In one particularly humorous and rambling inventory request response, Springs reported that he had taken over accounting because his bookkeeper had suffered a nervous breakdown, but sadly was not up to the task himself.[xiii] Springs dissembling response blamed his difficulties in accounting based on the fact that he had some frames in railway cars, some in temporary storage, and a few that he believed had “floated down the river from Mount Holly in the flood of 1916.”[xiv] Springs partially hid the fact that he was expanding operations at a time when New Deal policy, in general, favored large decreases in production in order to limit supply and bolster prices. However, Springs' letter written to President Roosevelt reveals that to him, the New Deal meant something very different than it came to mean in the sphere of public policy. Springs was proud to report wage increases for every employee (except himself, who didn't draw a salary until 1937), the ending of child labor practices, and an equal opportunity to work that did not exclude those “who have bad eyes, stiff fingers, or rheumatic joints.”[xv] However, Springs initiated these actions voluntarily, and seems to have conceived of the New Deal as representing a call to action by those citizens in a position to aid their communities, not as a sweeping government regulation initiative. Springs also fought unionization at his plants, but not without the full support of his employees. In part, Springs was aided by the simple fact that he was independently wealthy, and so in one regard his employees needed the plants to remain open much more than he did. However, Springs’ actions don’t fit with a man who didn’t need the plants to remain opened. Moving a loom to his basement, updating rather than scrapping the plants, and often being seen in his plants during the 3rd shift, usually on the floors rather than in his office,[xvi] demonstrated a personal concern that was reciprocated by the employees. An elderly woman, who had previously worked in the mill and needed her job back as the Depression threatened her livelihood, was given a job by Springs despite the hiring manager’s repeated denials of having work for her.[xvii] According to employee legend, the woman entreated Springs personally for the job one day in the street, which Springs responded to by instructing her to meet him at the mill gate the next morning. That morning, Springs had the desk chair removed from the manager’s office, brought to the floor, and instructed the women that her new job (complete with wages) was to sit in it until work was found for her.[xviii] True or embellished, these were the kinds of legends which could only be generated from genuine affection. In a very limited and somewhat anecdotal fashion, it is stories like these that represent the real people behind Fishback’s assertion that private employment had a much higher influence in raising the standard of living among workers during the Depression than New Deal policies.[xix] Unionization in the 1930’s was a hotly contested issue, and not always voluntary, as the Springs Cotton Mills clearly demonstrate. There was a serious belief held by union officials that every business within a sector must be unionized, whether they wanted to or not. Union agitators often came with guns and threats of violence. According to one employee’s recollection, Springs vowed to allow his workers to make the choice themselves, but pledged to, “move his bed into the office and stand siege with them,” should his workers want to resist unionization.[xx] In his tying of his own person well-being to that of his broader community, Springs inspired his workers to have more faith more in their boss, than in collective action against him, and as a result of the joint commitments of Springs and his employees, the Springs Cotton Mill Company never unionized. Despite the Great Depression, The Springs Cotton Mills property value grew every year from 1933 to 1940, and the total amount paid in wages and salary also tripled in the same timeframe.[xxi] The company’s net sales only posted one year of decline, understandably in 1938 when the national economy shrunk a second time. Of course, in many ways, the Springs Cotton Mills were uniquely positioned to immediately benefit from the initiation of World War II, although somewhat accidentally. Springs had stockpiled large amounts of textiles in order to keep his plants opened and prevent him from needing to cut production, and therefore employment. These textiles became immediately liquid as demand for cloth soared for wholesale production of military uniforms during WWII. This was however, an incidental boon to the Springs Company, not the explanation for its survival.[xxii] The history of the Springs Cotton Mill Company during the Great Depression runs counter to most traditional explanations for the end of the Depression. The sales and business figures for the Springs Cotton Mills demonstrated that the company was growing long before World War II production began. Additionally, the New Deal policies enacted during the period were certainly not helpful, and probably adversarial to the company. However, its degree of non-compliance (which was the highest among all South Carolina Cottom Mills) with those policies certainly gave Springs Cotton Mill Company an advantage, so it could be argued that the benefit to the company was in gaining a competitive edge against others who were conforming to government regulation. Therefore, at least on a case-by-case basis, it cannot be argued that New Deal policies were beneficial to the cotton mill industry. Whether or not they rescued the industry as a whole cannot be ascertained based on the story of one company. So then, it can be said that in this one case, in one community in South Carolina, the Springs Cotton Mill Companies, which had not yet been consolidated by Elliott at the time, were certainly a microcosm of the causes of the Depression. Shrinking availability of credit, bankruptcy of related investments, complacent business practices which took for granted the boons of the “Roaring 20’s” and collapsing demand almost ruined the company. Its escape from the Depression, however, defies explanation along the lines of normal macroeconomical theory. Rather is the personal success story of Elliott White Springs, and the thousands of employees who worked with and fought for the man who owned their company. [i] Elisha, Walter Y. “Standing on the Shoulders of Visionaries: The Story of Springs Industries, Inc.” Speech. 1993 South Carolina Meeting, The Newcomen Society of the United States, Rock Hill, SC. April 22, 1993. 17. [ii] Ibid. [iii] Ibid. [iv] Ibid, 13-14. [v] Pettus, Louise. “Elliott White Springs: Master of Mills and Many Other Things,” in The Legacy: Three Men and What They Built, Speech. University of South Caroliniana Society, Columbia, SC. May 22, 1987. 25. [vi] Pettus, Louise. The Springs Story: Our First 100 Years, Springs Industries, Inc: Fort Mill, South Carolina, 1987. 89. [vii] Ben Bernanke argued that greatly tightening lending practices was a large contributor to the radical collapse of the entire business sector. Loans were still available, but only given to those who were considered “safe.” This explains why interest rates declined but were not received with a corresponding increase in business activity, as is normally the case when interest rates decrease. In this case, Elliott White Springs, whose business acumen had been called into question by his father, and who had a reputation as an author, war hero, and playboy millionaire, but not as a businessman, faced a serious crisis for the continuance of his business which needed increased inflows of capital for modernization, but was considered far too high of a risk to actually secure loans from the New York firms. Bernanke, Ben S. "Nonmonetary Effects of the Financial Crisis in the Propagation of the Great Depression." The American Economic Review 73, no. 3 (1983): 257-76. [viii] Pettus, The Legacy, 26. [ix] “Indexes of Manufacturing Production, by Industry Group: 1889 to 1954,” in Bicentennial Edition: Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, United States Department of Commerce, 668. [x] Pettus, The Springs Story, 95. [xi] Ibid, 27. [xii] Ibid, 27-28. [xiii] Ibid, 101. [xiv] Ibid. [xv] Springs, Elliott. “Letter to Franklin D. Roosevelt, July 28, 1933” in The Springs Story, 97. [xvi] Pettus, The Legacy, 26. [xvii] Ibid, 27. [xviii] Ibid. [xix] Fishback, Price. “The Newest on the New Deal.” Essays in Economic & Business History, Vol. 36, 2008. 5 [xx] Pettus, The Legacy, 29. [xxi] “Springs Growth,” in Our 75 Anniversary: The Story of the Springs Cotton Mills 1888-1963, Springs Industries, Inc: Fort Mill, South Carolina, 1963. n.p. [xxii] This point is, in many ways commiserate with Christina Romer’s assertion that gold influxes from Europe in the lead up to WWII led to economic conditions that benefitted American business. It was therefore in this case, not the mobilization of the American industrial sector for wartime production that rescued America from the Depression, as is the typical historical narrative, but rather other factors related to the War that influenced the economy. The Springs Cotton Mill Company did not need to sell its stockpiled items in order to escape the Depression, but it was a definite beneficiary of increased demand for its products. Romer, Christina D. "What Ended the Great Depression?" The Journal of Economic History 52, no. 4 (1992): 757-84. Charles A. Conant had a very important role in America’s transition to a global, imperial power. Notable libertarian writer, economist, and historian Murray Rothbard details the various actions that Conant took to enthusiastically facilitate the expansion of the United States into the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and other territories over which the US gained influence in the wake of the Spanish-American War. Perhaps the most damning indictment of Conant was not his failure, but rather his great degree of success in bringing these regions of the world under American control.

Calls for Imperialism Conant believed that the urge for economic imperialism was irresistible, drawing clear connections between Rome, the British Empire, and contemporary America, which he believed was “about to enter the path” of these prior empires.[i] Further, according to Conant, the imperialistic tendency which he observed in America was clearly and firmly rooted in race theory, and his belief that the American civilization was more developed, and that this gave a moral superiority to their domination of lesser races.[ii] According to Conant, economic domination as a place to sell excess goods was nothing less than necessary for the continuation of the prosperity of the American (and other similarly developed Western) nation(s). We are closely acquainted with the image of Cecil Rhodes triumphantly straddling the continent of Africa, holding a telegraph wire and asserting his domination over the continent. Westerners have, fortunately, come to be very critical of this act of domination, under which rested strong racial supremacy theories that convinced Rhodes that “[the British] are the finest race in the world and that the more of the world we inhabit the better it is for the human race.”[iii] In essence, the world should be grateful and, in fact desperate, to be subjugated by the British, because subjugation brought “the most despicable specimens of human beings. . . under Anglo-Saxon influence.”[iv] Furthermore, Rhodes justified conquest in economic terms, pointing to “the extra employment a new country added to our dominions gives.”[v] In schools, histories, and various other remembrances of our shared past, Rhodes receives few positive mentions, and is known to many as an unapologetic apostle of Western Expansion. According to Conant, the essential problem was that Westerners saved too much money.[vi] If nobody saved anything, there wouldn’t be a problem, because this would allow the economy to continue developing, but every dime saved, according to Conant, led to an unconsumed product, which led to lower demand and inefficiencies. Rather than changing consumer or spending habits in America, Conant reasoned it would be much easier to force other nations to purchase American-made products. Centralization of the American State Rothbard noted that “Conant was bold enough to derive important domestic conclusions from his enthusiasm for imperialism.”[vii] Conant was willing to sacrifice principle as well as the well-being of those in other parts of the world for the continued growth of the American economy. He fully recognized that his principles were at odds with the Founding principles of self-rule and limited government, but Conant believed that that pragmatic American economic interests should supersede ideological commitments.[viii] To this end, Conant wrote a brief biography of Alexander Hamilton, the Founder whose own views tended to assist Conant the most in his attempts to justify expansion both domestically and abroad. Conant saw Hamilton’s enduring contribution to the United States primarily in terms of his advocacy for a strong federal government: “It is certain that the conditions of the time presented a rare opportunity for such a man as Hamilton, and that without some directing and organizing genius like his, the consolidation of the Union must have been delayed. . .”[ix] Throughout the book, Conant repeatedly credits Hamilton with the strength of the federal government and plainly believes that Hamilton, more than any other Founder, helped to shape the eventual government of his own contemporary days. Hamilton was a natural fit for Conant’s own domestic arguments, but also fit nicely into his imperialist framework. According to Conant, Hamilton “was among the first to maintain that the United States should have complete control of the valley of the Mississippi” and “the admirers of Hamilton credit him with a still wider vision of the future power of the United States, which was eventually to bear fruit in the Monroe doctrine.”[x] Conant, guilty of a great deal of anachronism, connected Hamilton not only to the Monroe Doctrine of the early 1800’s, but also to American Imperialism in general by linking the statements of “Secretary Olney in 1895, that ‘to-day the United States is practically sovereign on this continent, and its fiat is law upon the subjects to which it confines its interposition.’” with Hamilton’s own words “in ‘The Federalist,’ before the adoption of the Constitution, that "our situation invites and our situation prompts us to aim at an ascendant in American affairs.’”[xi] According to Conant, Hamilton would have approved. Monetary Imperialism Hamilton’s advocacy for federal currency created another natural fit for Conant, who sought to expand the influence of the US Dollar abroad. The Philippines had a stable currency based on Mexican silver dollars which the Spanish had unsuccessfully attempted to discourage for decades.[xii] The difficulty in converting silver to American currency, then based on Conant’s preferred gold, led to “many complaints. . .against what [American officers and civilians] considered excessive rates [of exchange] charged by the banks.”[xiii] Conant’s monetary policies, however, were more subtle than his generalized views on Imperialism. Throughout his essay, The Currency of the Philippine Islands, Conant seems to advocate for a monetary policy which was acceptable both to the United States and the Philippino people without particular bias to one or the other. He candidly admits that having all nations in the world on one metal standard would be the best-case scenario for the Western nations, but stops well short of actually advocating that this should be forced upon the Philippines or any other American territorial holding.[xiv] However, according to Rothbard, this was just a “cunning plan” to “replace the full-bodied Mexican silver coin” with “an American silver coin tied to gold at a debased value.”[xv] According to Rothbard, it would essentially net U.S. banks large reserves which they could then use to issue paper currency, and serve as the standard for the way of “exploiting and controlling Third-World economies based on silver.”[xvi] In essence, Conant had discovered a way to place poorer nations on a gold standard that clearly benefited nations already on a gold standard while appearing to do nothing of the sort. Ultimately, the new US currency, the “conant” was the new currency in the Philippines, having been successful by “force, luck, and trickery.”[xvii] Lessons from American Imperialism Conant’s monetary plan, then, was a subtly disguised accomplice to his broader and more naked ambition for the expansion of the US Federal Government, domestically and abroad. His schemes took nothing into account but the betterment of the specific big-business interests within America, to the detriment of many other interests. Studying the actions and philosophy of Conant is a stark reminder of what happens when a man’s only principle is pragmatism. Conant argued persuasively and effectively for Imperialistic policies, fully cognizant that his plans flaunted the principles upon which America had been founded. It is unfair to blame this fully on Conant, he was just a product of the more generalized thinking of the Progressive Era. There were Charles A. Conants in education, finance, politics, the military, and every sector of public life; men (and women) for whom pragmatism was the chief ideal. In fact, I argue that in this respect, the Progressive Era has never ended. Ideals and principles are in short supply in modern American civil discourse; they are tiresome obstacles that prevent high-minded obstructionists from being willing to cooperate with Progressive politicians (of both parties) to “get things done.” The ideas advanced by Conant and other Progressives succeeded in leading to American political domination of the world for a time, but the true legacy of their Era has been the almost complete conquest of the American Public Spirit, and the ideals of the Founders for many of whom principle was more important than pragmatism. [i] Conant, Charles A. "The Economic Basis of "Imperialism"." The North American Review 167, no. 502 (1898): 326 [ii] Ibid. [iii] Rhodes, Cecil. “Confession of Faith.” 1877. [iv] Ibid. [v] Ibid. [vi] Conant, “The Economic Basis of Imperialism”,” 330. [vii] Rothbard, Murray. “The Origins of the Federal Reserve.” The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics, 2, no. 3 (1999): 21 [viii] Rothbard, 21. [ix] Conant, Charles A. Alexander Hamilton. Ebook: Project Gutenberg. New York: Houghton, Mifflin, and Company, 1901. [x] Ibid. [xi] Ibid. [xii] Conant, Charles A. "The Currency of the Philippine Islands." The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science20 (1902): 44-45. [xiii] Ibid, 45. [xiv] Ibid, 531-32. [xv] Rothbard, 27. [xvi] Rothbard, 28. [xvii] Rothbard, 29. To make certain claims about the labor experiences of women as a demographic subset in America obscures certain realities about regional differences that led to different experiences of women in different parts of the country at the same time. Although this blog focuses just on women, it should be stated as obvious that the same is true for other demographic subsets such as race, and therefore any attempt by any historian or economist to explain the experiences of these groups of Americans without accounting for regional differences as well confront the possibility of a misapplication of their data.

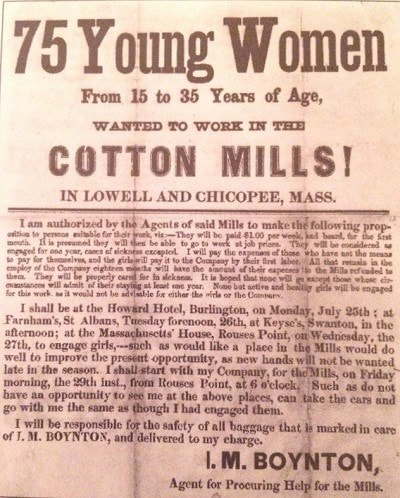

According to the Historical Statistics of the United States, Colonial Times to 1970, the number of Americans employed in non-farming occupations increased by about 50% during the first decade of the 1900’s.[i] During the same time period, the number of farm workers in America increased by only 2%, meaning that almost all of the employment growth experienced at the turn of the century was from industrial, not agricultural jobs.[ii] This blog post will specifically look at the demographics of two different states, South Carolina and Connecticut, in order to illustrate the significant differences in the participation rate of women within these regional economies. The increase of jobs in South Carolina at the turn of the century was about 30%, and the increase in Connecticut at the same time was similar.[iii] and the respective size of each state’s working population was roughly similar numerically as well.[iv] Based on these simple metrics, it can therefore be concluded that the growth of South Carolina and Connecticut were rough approximations of one another and therefore these particular variables can be considered similar. As measured simply by the number of persons engaged in the economic activities of the state, the growth between 1900 and 1910 within South Carolina and Connecticut were also roughly the same. In fact, each state was chosen as a representative of two distinct regions, but they were specifically chosen in this comparative analysis because of how similar they were in the total number of people employed and the changes evidently experienced in both economies over that time period. What is interesting about these statistics is that they are not as similar as the overall numbers suggest. In Connecticut, the number of employed men outnumbered women 3:1, whereas in South Carolina it was much closer to 2:1.[v] Even more interesting, was the increase in female participation in the labor force during this decade. There was almost a 50% increase in female employment in South Carolina during the decade, while male employment was closer to a 15% increase.[vi] Even more interesting however, is that when evaluated based on sex rather than in aggregate, one finds again that in Connecticut, the female and male labor forces expanded at the same rates as in South Carolina.[vii] When evaluated on a national scale, one finds that the growth in female and male employment in both states was roughly in line with the national averages at the time.[viii] This proves that there was nothing different in how each economy was changing during that time period, but there was a significant regional economic difference that led to a much higher rate of participation among South Carolinian women. It might be assumed that this was due to the traditional assumptions about the agrarian nature of the South Carolinian economy; perhaps women worked more in South Carolina in agricultural activities? This hypothesis is rendered unlikely given the fact that the total acreage utilized for farmland in South Carolina decreased from 1900 to 1910 by about 2%.[ix] If agrarian activity was the reason for the difference, one would expect to see small reductions in the female workforce, not the massive increases that were realized relative to men during the same time period. The Connecticut reduction in overall farm acreage also decreased by close to the same proportion.[x] Therefore, the discrepancy in employment of women between the two states had more to do with the type of non-agricultural employment that was available in the two states. Furthermore, since both states seem to have developed in generally the same way during the first decade of the 20th century, it can be further concluded that the main discrepancy in female participation in workforce pre-dated the turn of the century. 62.2% of all employees who held manufacturing jobs in South Carolina worked in a Cotton Mill, or in the manufacture of cotton-related products.[xi] This is such a large proportion of the economy that if the demographics of this one industry did not mirror the overall demographics of the state, it would dramatically change them from the national averages. It can therefore be assumed that the proportion of men and women working in the cotton industry was a fair approximation of the state average (or perhaps even slightly more than average), and therefore it can be further concluded that women constituted a significant portion of the labor force within the cotton industry in general, and this explained their greater employment rate within the SC economy. The production of cotton goods within the Connecticut economy constituted a mere 6.8% of the total economic production, whereas metallurgical outputs (Brass, foundry, and machine-shop products), the two largest sectors of the Connecticut economy, accounted for almost 26%.[xii] It can therefore be surmised that at least one large factor in the differences between the South Carolina and Connecticut economies that led to much greater female participation in South Carolina was the type of manufacturing opportunities that were available to the general workforce. It makes sense that women would be more likely to be employed in the textile manufacturing industries as opposed to machine and metallurgical industries. Of course, this brief review of these census records does not rule out that there were other factors that may have contributed to the higher rate of female participation in South Carolina. There may have been other economic factors (i.e. the need for a dual-income family to meet general requirements for a standard of living) that led to higher female participation in the workforce. Nor does this evaluation prove causation; it is also possible that female willingness to work was the driving force on the supply side of the labor curve that led to the development of the cotton industry in South Carolina. This seems counterintuitive given geographical considerations, but it remains possible without deeper analysis. Notwithstanding the potential shortcomings of this brief economic survey, it can be concluded that the rate at which women participated in the workforce relative to men was significantly different in Connecticut and South Carolina, and that it was strongly linked to the type of industrial production in both regions. Potentially even more interesting is the traditional assumption that female participation in the workforce is a strong indicator of the overall condition of women's rights and more equitable social conditions. For this to be true, one would be forced to admit that South Carolinian society was far more progressive than Connecticut at the turn of the 20th century. Since this argument is likely to be refuted by a host of other data, one must admit that while female employment may be connected to gender equality in the 21st century, it is definitely anachronistic to make the same argument about early 20th century America. [i] US Census, Labor Force, Series D 1-10. Labor Force and its Components: 1900 to 1947. Department of Commerce and Labor, 1975. 126. [ii] Ibid. [iii]Ibid. Series D 26-28. Gainful Workers, by Sex, by State: 1870 to 1950. 129-130. [iv]Ibid. [v] Ibid. [vi] Ibid. [vii] Ibid. [viii] Ibid. Series D 75-84. Gainful Workers, by Age, Sex, and Farm-Nonfarm Occupations 1820:1930. 134. [ix] Supplement for South Carolina of the 1910 US Census, Department of Commerce and Labor, 1910. 608. [x] Supplement for Connecticut of the 1910 US Census, Department of Commerce and Labor, 1910. 605. [xi] South Carolina 1910 Census, 686. [xii] Connecticut 1910 Census, 623. We spend a large portion of our time focusing on major battlefields and large museums that offer the spectacular history that we remember from our school-aged history classes. I remember visiting Gettysburg battlefield as a high school freshman, (as was typical for most students in Pennsylvania) and looking at the fields and monuments had been erected. Thanks to Ronald Maxwell’s documentary, Gettysburg, I could literally picture the battle which had taken place on the field, and there felt the surreal experience that I will simply call hearing the whispers of history. I was able to feel a connection to the shared past of our country, and in on that day, history became present to me, if only softly. But history is all around us, and we need do is learn about it, and go to one of hundreds of historic sites are in our immediate vicinity in order to experience the same. One such place is a little-referenced site in Bedford County which is connected to Thomas Jefferson known as “Poplar Forest.” Poplar Forest was originally the property of Francis Callaway, who simply called it “the forests.”[i] Callaway’s son was a famous colonel who fought in the French and Indian War and the American War for Independence.[ii] He successfully defended a fort in Boonsboro, Kentucky during the War for Independence against the Indian chief Blackfish and 11 Frenchmen (who apparently hadn’t gotten the memo that the French and Indian War was over and France was now an ally of the American colonists).[iii] At another time, Col. Callaway and Daniel Boone had led two successful parties to recover their daughters from Indian capture, presumably becoming the inspiration for James Cooper’s The Last of the Mohican’s.[iv] History whispers to remind us that ordinary men become giants, simply by acts of courage. The Callaway family sold the land to Thomas Jefferson’s father-in-law who, upon his passing, transferred the property to Jefferson’s wife.[v] The Jefferson’s operated Poplar Forest as a plantation, which was a significant source of income to the family throughout Jefferson’s life.[vi] During the War for Independence, Jefferson briefly fled to the retreat during 1781, because Monticello was being threatened by the British army.[vii] I had always known that certain state leaders had needed to evacuate in order to be spared from the British during the War, and most people would easily connect Jefferson’s precious Monticello to certain memories, but if you are like me, then you never gave a second thought to where Jefferson went at that time. You would if you stopped to learn the history of Poplar Forest. History whispers to tell us that it surrounds us everywhere, and we don’t have to travel to the most expected places to find it. Jefferson spent a significant amount of time at Poplar Forest. He left Washington in 1806 to oversee the laying of the foundations of the octagonal structure which is still on the property today.[viii] It is inconceivable to us that a president would leave Washington, DC where he is literally unable to be reached for hours or days in order to oversee something so menial. Family, and family affairs were equally important as public obligations, and in fact our Founders knew that it was self-defeating to the purpose of our new republic if we sacrificed family for country. History whispers to remind us that we’re ignoring something precious in our new age of globalization, technology, gadgets, and distraction. Jefferson had the house built to exacting specifications. Like Monticello, Poplar Forest’s primary architectural feature was a perfectly octagonal main home, although unlike Monticello which featured the octagon only as a central feature, Poplar Forest was originally built as a perfect octagon with no additional geometric shapes added to the structure.[ix] The house was built to exactingly specific rules, following the classical order for most everything. Jefferson commissioned a sculptor to do the architectural frieze in the classical style.[x] Yet Jefferson wished to explore his own personal taste in the space, so he broke classical rules by adding ox skulls to the frieze and sacrificed formality and practicality by having the staircases enter into bedrooms on the upper level.[xi] History whispers to remind us that sometimes personalization is a worthy investment, even when doing so diminishes the value in the eyes of others. "I can indulge in my own case, although in a public work I feel bound to follow authority strictly." |

AuthorNathan Gilson is a Social Studies Teacher in South Carolina with over 10 years of experience in the public school systems. He has taught US and World History courses, and is currently working toward a Ph.D. in History from Liberty University. Archives

April 2021

Categories |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed